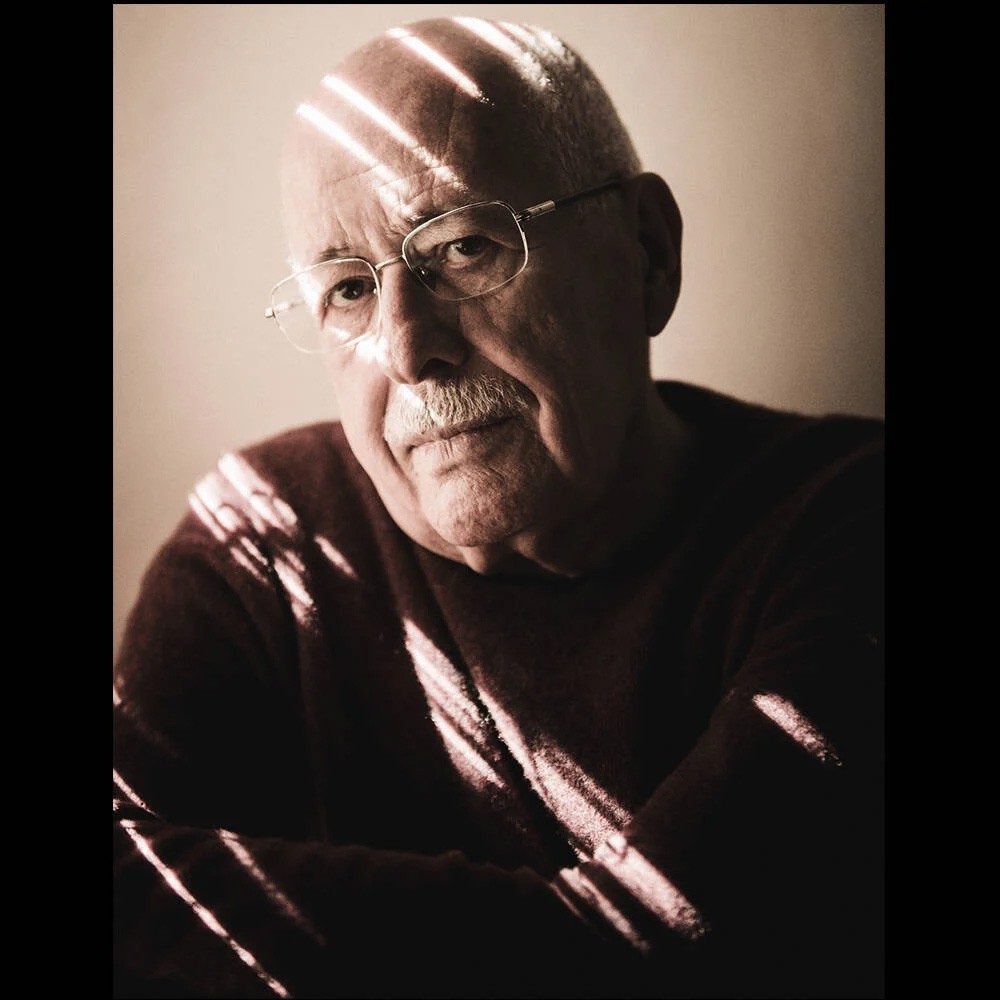

Winner of the most important prize in the Portuguese language. Professor, essayist and writer. Brazilian. 86 years old. Freedom of creation is the legacy Silviano Santiago wants to leave behind. It was this freedom that the Camões Award jury valued in the author who questions language and reflects identity. “Em Liberdade” was considered one of the works that best represents 20th century Brazilian fiction, poetry and essays. The other awards, such as “Oceans”, in 2015, and the “Jabuti”, after two years, reinforce the uniqueness of a name that challenged the Eurocentric perspective on Brazilian literature. To PLATAFORMA, Santiago says it is decisive for the Portuguese language that Brazil becomes an international protagonist. “That is the path, which Bolsonaro has totally denied,” he says

-He said the award came “in a difficult moment for the world and for Brazil”. What role does, can Literature play?

Silviano Santiago – At the time of the news, emotion was restrained. Today I can already say that it is full. We had a beautiful victory in the elections. Literature doesn’t intervene, eventually it helps to reflect. My writing follows very closely what happens. My first book – “Em Liberdade” [Graciliano Ramos’s alter-biographical fiction when he is released] – was published when Brazil was coming out of a second dictatorship, the military one of ’64. The book was meant to help people think about what freedom is when an authoritarian regime ends.

-The Camões Award distinguishes authors “whose work contributes to the projection and recognition of the literary and cultural heritage of the language. What legacy would you like to leave behind?

S.S. – That of freedom of creation. Tom Stoppard, a great English playwright, once asked me what it was like to write in a language that few people read. He just told me that when he wrote he had to make sacrifices because he knew it would be translated and that this constrained him. Writing in Portuguese gives me absolute freedom.

-Although I recognize its quality, it implies difficulties that others do not face.

S.S. – Writing in Portuguese is similar to writing in German or Russian because of the difficulty of spreading the word and the need to translate the text because there are not enough readers. But the disadvantage at this point becomes an advantage at another. Murilo Rubião’s “Pirotécnico Zacarias” begins like this: “In truth I died. In conversation with the translator who translated it into French, I asked her why she had not translated the first sentence. She replied that it makes no sense in French because it is an unlikely narrative. And what is an obstacle in Portuguese can become a strength, it just depends on the genius of the authors and, luckily, our authors have been quite brilliant. Clarice Linspector, for example. Would there be anyone who would write like her back then? No, and the proof is that she is a posthumous author. She is modern before her time.

-Paloma Vidal, who translates it, describes you as an author who “questions what it is to make literature, what it means, and the political implications.” Do you see yourself?

S.S. – It’s not just me, it’s my generation, which will be known for having thought about language. Being after Freud, Nietzsche and Marx, we already knew that no language is spontaneous. The formalism of the poet João Cabral de Melo Neto is symptomatic. If you read a 19th century author, the characters have the same language. In our generation each character has a language. There is an ‘I’, which is matricial, and several ‘I’s’, which are co-adjuvants. It is the lesson of Fernando Pessoa, that we are not only one.

-You are also considered a pioneer in transdisciplinary and post-colonial analysis. What kind of turn did you advocate?

S.S. – Focault says that the important thing to question about a book is the relationship between work and author. I have always been very concerned in working on that enigma. My biographical data are very relevant in my path. In the 1960s, I won a scholarship from the French government and went to do my doctorate at the Sorbonne. When I arrived, I got a fright because what I saw did not coincide with what I had read about France. It was the height of the Algerian War. And I discovered that there was a colonial Brazil. The most complete book on Brazilian literature, by Antônio Cândido, begins in 1800. I realized that I hadn’t read anything about the colonial period, at the same time that the city was exploding, that the police were not asking me for documentation, but were asking the darker Brazilians. I realized colonialism and that I had to think about it.

-And?

S.S. – One of my interests was exactly to investigate what was written in Brazil in the colonial period. “The in-between-place of Latin American discourse” is the result of this immersion and philosophies of difference. I wanted to understand literature in a different way. The idea was not to dismiss the post-eighteenth-century production, but – and here a very relevant concept comes into my thinking – to develop the idea of ‘supplement’ instead of ‘complement’. I was possibly one of the first decolonialists – I didn’t use the word. I anticipated a production. Every book of mine is different because it is the product of an investigation, reflection. I feel an evil and when I feel it I want to dig into it, to go inside and find out why I feel this way, which is this weirdness that can be said to third parties, fourth parties, fifth parties, and that will bother many. I’ve been really swarmed by the critics.

-You say that “the notion of identity in a complex and rich country like Brazil, which has experienced violence such as the indigenous genocide and black slavery, needs to be inclusive, that is, it is necessary to work with forms of identity and not a single identity. Is that path being taken?

S.S. – Very little by little, and the Bolsonaro government was a great delay. Lula’s was the one that most sought inclusion. In the 50s, when I was studying at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, there was not a single black or indigenous person, much less professors. The teaching of literature itself started in the 18th century, this was the milestone that Brazilian literature was considered to have become. This is not a misconception. It is a way of thinking about Brazil from a Eurocentric perspective.

-You stated that Bolsonaro represented a concrete threat because of his connections with the extreme right. Does the threat cease to exist now that he has lost?

S.S. – Of course not. Only the democratic key has been turned. I only have one fear: the excessive judicialization of politics. How can this necessary partner that is Justice intervene in a less bureaucratic and more balanced way? Take the example of the United States, Trump’s shenanigans – rascality would be the right word – are endless. He will never testify in the Senate and there is nothing to stop him from being a candidate for the presidency. I fear that this change in Brazil will be greatly hosed. I used to imply the useful vote. Now I understand it. Without him there was no possibility of facing the Bolsonarist wave.

-Lula is not seen as an immaculate politician. There are those who consider that the choice was between the lesser evil and that none would save Brazil.

S.S. – Moro [former Minister of Justice] is another flagrant example of the judicialization of politics. It was terrible for us, for Europeans and in particular for Africans because it shut down all the big Brazilian companies that were providing a very interesting service to Brazil, of course – because we are not so generous, we know that there is evil in this Brazilian neo-colonialism in Africa. We can discuss this, but what happened was that all the firms had to leave. I was in Angola at the time and who replaced them? The Chinese. Moro gave away the Lusophone countries to China for free. He could have told the Odebrecht company to pay I don’t know how many millions, judge responsible, but the workers were not fired and the branches were not closed. What bothers me about the judicialization of politics is not that the corrupt are found, but that everyone ends up affected. I would like some thought to be given to Lula’s culpability. I’m not saying they are exempt, but there are ways and ways to pay. Justice works lame.

-In his victory speech, Lula said, “I want more books and fewer guns, because culture feeds the soul.” Will you accede to the challenge?

S.S. – I have always been a Lulista. I admire a lot how he governed the country. He believes in Culture and, in first place, in Education. He has made extraordinary programs in favor of the less favored. Literature’s great weapon is to awaken. It’s a good way to get what you want. Culture is at a standstill, in Education we have had four ministers. We are in a state of calamity. And going back to the language issue, it is fundamental that Brazil becomes an international protagonist. This is the path, which Bolsonaro has totally denied.