On October 1, 1949, the PRC was founded following Mao Zedong’s victory over Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang, which retreated to Taiwan. Mao Zedong, the historical leader of the Communist Party of China, proclaimed the creation of the Republic in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. How did Macau and Portugal react to this monumental political earthquake that forever changed China’s future?

“When the news of the founding of the PRC reached Macau, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) had not yet liberated the Guangdong province, Hainan province, and other surrounding areas,” says Agnes Lam, director of the Macau Studies Centre at the University of Macau.

At that time, “Macau was still under Portuguese administration and maintained diplomatic relations with the Kuomintang. However, despite this diplomatic position, there were unofficial celebrations marking the foundation of New China in Macau, highlighting local support for the Communist Party.”

According to the researcher, local institutions such as Hou Kong Secondary School and Kiang Wu Hospital, which had ties to the Communist Party since the Sino-Japanese War, were among the first to express their loyalty to the new government. Agnes Lam recounts that upon learning that the red flag with five stars had been designated as the national flag, the then-director of Hou Kong Secondary School, Tou Lam, made efforts to obtain one.

“However, due to administrative restrictions, the nearby district of Zhongshan received only three national flags. Faced with this scarcity, Tou Lam took the initiative to create a flag herself, using a published image as a reference and sewing it overnight with red and yellow fabrics she had acquired.”

On the day of the proclamation, Tou Lam organized a flag-raising ceremony at her school, and early in the morning, she brought a radio to the schoolyard in preparation for the event. At 3 PM, while the national anthem played from Tiananmen Square in Beijing, the handmade red flag with five stars was raised by teachers and students, symbolizing their participation in the birth of New China.

PRC flag raised by Hou Kong Secondary School

The display of the flag in Macau did not go unnoticed by the Portuguese administration, which summoned Tou Lam and interrogated her. “Despite the pressure, she firmly declared her patriotic feelings and her right, as a Chinese citizen, to celebrate the founding of the new nation,” Lam recounts.

On October 10, 1949, it was the turn of Kiang Wu Hospital to celebrate the occasion under the leadership of its then-president, O Lon. In the hospital auditorium, portraits of Dr. Sun Yat-sen and President Mao Zedong were displayed, flanked by red five-star flags. The lyrcis of the PRC national anthem and the “Three Great Disciplines and Eight Points of Attention” were prominently displayed, along with celebratory slogans.

However, according to journalist and writer João Guedes, in 1949, most Chinese institutions in Macau were linked to the Kuomintang, making the founding of the PRC a “shock” to the majority of the community, including the Portuguese community and the Portuguese government of Macau, which “initially did not know the intentions” of Mao’s new government towards Macau. “There were no major displays of joy because most people supported the Kuomintang. Support for the communists in Macau was minimal,” Guedes explains.

Mao preserves the Status Quo

months before the official declaration of the PRC, in contacts with Soviet representatives, Mao had already commented that regarding Macau and Hong Kong, it would be “necessary to adopt more flexible solutions or a policy of peaceful transition, which would require more time.”

According to a study by political scientist Moisés Silva Fernandes, Portuguese rulers in Macau and Portugal feared the collapse of the small enclave with the growing dominance of the Communist Party of China (CPC) within, marking the beginning of the end of Portuguese Empire rule. Mao’s government officially claimed a revolutionary, anti-colonialist, and anti-imperialist political orientation, which boded ill for the Portuguese administration of the territory, in place since the 16th century.

In the first half of 1949, there was already a mass exodus of the Macanese community from Shanghai, instilling fear in Macau and among Portuguese decision-makers in Lisbon that the region would face a similar fate. Portuguese authorities even reinforced the Macau garrison with 6,000 troops.

It is hard to know if reason will be enough to avoid violence and find a path of respect for rights and reconciliation of interests,” said António de Oliveira Salazar, the highest figure in Portuguese politics at the time.

According to Moisés Fernandes’ study, months before the official declaration of the PRC, in contacts with Soviet representatives, Mao had already commented that regarding Macau and Hong Kong, it would be “necessary to adopt more flexible solutions or a policy of peaceful transition, which would require more time.”

For Mao, it might be more advantageous to explore the status quo of these territories, especially Hong Kong, to develop China’s relations with the outside world.

The new Chinese leadership was “willing to discuss the establishment of diplomatic relations with any foreign government based on the principles of equality, mutual benefit, and mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty,” provided that such a government was willing to sever ties with the “reactionary Chinese,” namely the Kuomintang forces.

To this end, on August 28, 1949, the CPC’s Department of Commerce created the Nam Kwong Trading Company, with the official goal of promoting trade ties between Macau and mainland China. According to Moisés Fernandes, the company functioned as an unofficial representative and “parallel government” of the People’s Republic of China in Macau administered by the Portuguese.

Beijing and Mao took care to reassure the population of Macau […] that they could live their normal lives without worrying about the profound transformations taking place in China,” notes João Guedes.

“This coincided with the arrival in Macau of remnants of Kuomintang forces, which were disarmed by the city’s garrison as they entered through the Inner Harbor and the Barrier Gates, placed in temporary camps before proceeding to Taiwan where the Nationalist government took refuge.”

To persuade the Portuguese administration of Macau and the Lisbon government of China’s interest in maintaining the status quo in the city-state, Chinese authorities utilized various channels.

To avoid misunderstandings arising from the PLA’s cleanup operations against the Kuomintang (near Macau), Commander Uong Iok, president of the political-military administrations in the region, sent a message to Carlos Basto, the Portuguese deputy commissioner of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service on Lapa Island, and to Macau Governor Albano Oliveira, explaining the policy in place regarding Macau and Portugal.

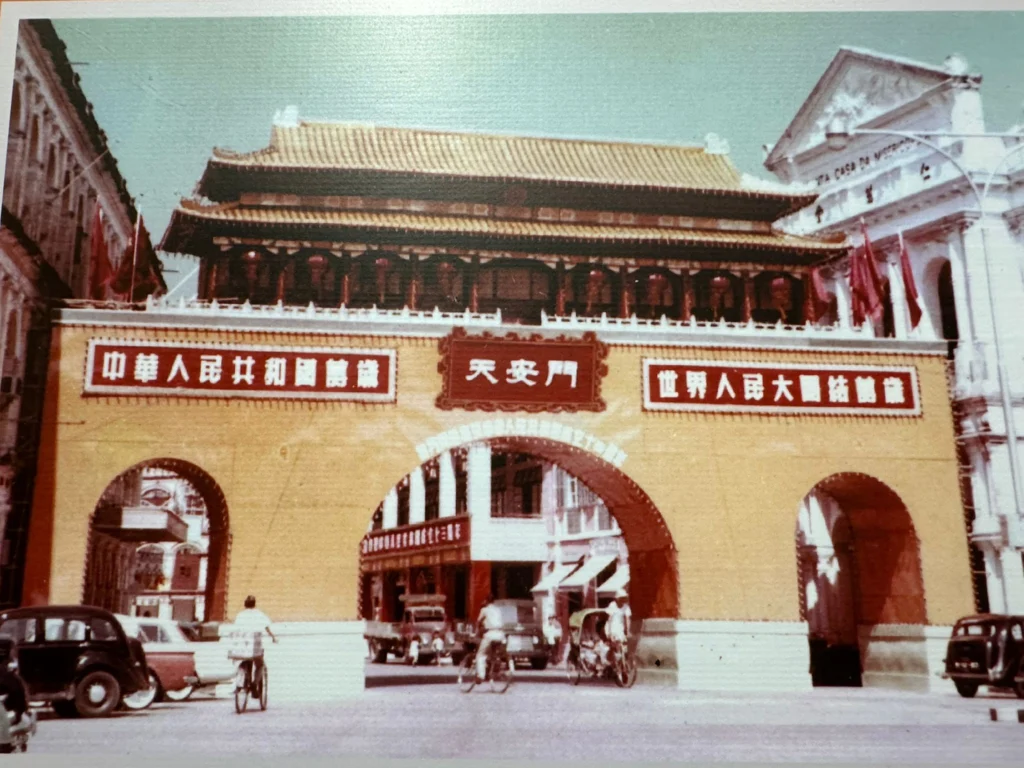

Raising October 1st celebration arches became an annual tradition in the city

“The Chinese communist authorities will respect Macau’s neutrality, and no member of the PLA will attempt to enter the colony in uniform […] Secondly, river links and others between Macau and China will continue as before,” Iok said at the time.

According to Moisés Fernandes, “for a period of 16 years, between 1949 and 1965, Mao Zedong’s regime did everything in its power to maintain a policy of status quo regarding Macau. The small city-state was politically, financially, and commercially important to China, and therefore, it conditioned its policy towards the enclave, even when it was heavily criticized by Moscow, as happened during the Sino-Soviet split,” he describes.

The maintenance of the city’s status was guaranteed, with the Chief of Staff of the Portuguese garrison in Macau, Captain Francisco da Costa Gomes, reducing the forces sent from Lisbon by half between late 1949 and 1951.

Too small for both

According to Agnes Lam, in November 1949, there was a significant public celebration in Macau: the erection of an arch in front of the Ping An Theater on Almeida Ribeiro Avenue. This arch, adorned with large portraits of Mao Zedong and Zhu De, marked the first structure of its kind in Macau related to the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

This act not only symbolized local support for the new communist regime but also served as a focal point for the expression of Chinese nationalism under Portuguese colonial rule. The demonstration caused discomfort among Kuomintang supporters in Macau, who, in response, began to assert their presence more forcefully by constructing their own arches at both ends of Almeida Ribeiro Avenue.

These initiatives occurred annually, starting in late September and continuing through October, transforming Almeida Ribeiro Avenue into a visual battleground of political ideologies.

First October 1 commemorative arch in 1949

“On National Day in 1950, despite economic difficulties, pro-CCP forces in Macau continued to erect celebratory arches,” Lam recounts. According to the researcher, this tradition not only “persisted” but also “expanded” over time.

After the founding of the PRC, the Portuguese government continued to recognize only the Kuomintang government in Taiwan, and October 10, 1911, the date of the founding of the Republic of China, continued to be celebrated by the nationalist faction in Macau.

“Supporters of China continued to discreetly live their lives, and it was only in 1951 that the first pro-CCP institutions emerged, including the Macao Daily newspaper and Nam Kwong,” Guedes notes.

The existence of two factions within the community led to increased tensions and occasional confrontations between the two groups in the streets.

The political and social turmoil within China during the Cultural Revolution would eventually pull Macau from this stagnation, leading to the ‘1,2,3’ incidents in 1966. A long embargo imposed by the Portuguese administration on the construction of a school in Taipa resulted in riots and confrontations that would take about two months to resolve.

One effect of the ‘1,2,3’ incident was the near-total loss of control by the Portuguese authorities over the Chinese community and the acceptance of the expulsion of any organization in the city affiliated with the Kuomintang and the government of Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan.

Macau 1,2,3 incident in December, 1966

According to former historian and commentator Camões Tam, between 1949 and 1966, the Kuomintang’s presence in Macau “was still considerably strong,” but after the ‘1,2,3,’ the Nationalist Party was effectively expelled from the city, with the CCP describing Macau as a “semi-liberated zone.”

“Since then, the CCP has effectively governed the Chinese population of Macau under the principle of One Country, Two Systems,” emphasizes the historian. Thus, October 10 ceased to be officially celebrated and was replaced by commemorations of the founding of the PRC on October 1.